We have about 1300 primary documents on Encyclopedia Virginia. In addition to selecting documents to digitize and transcribing and proofreading those resources against originals, my work is to write a header paragraph that contextualizes each primary document so that visitors to the site have enough information to learn from the document.

Before my time at the encyclopedia, K-12 teachers persuaded us to include primary documents in the site. They were using more primary documents in the classroom and wanted to have a place to send students to read them. Their suggestion was to have only the bare-bones information in the header paragraph in order to leave as much of the interpreting up to the students as possible.

However, students are not our only audience and I think everyone could benefit from some clues on how a person’s positionality has shaped their writing. And in the header paragraphs I am trying to do that while leaving plenty of room for visitors’ own analysis. Do we give visitors enough information to be able to understand the subjectivity of primary document’s author? If a document has a demeaning descriptions, does the header clearly contextualize them to point out the derogatory nature of the description? It seems important to explicitly point out the biases of the particular era, publication, or writer otherwise some will accept the description as mere fact.

With laws as primary documents, I try to add details about how they fit into the legal and social history of Virginia, what change it is enacting. For example: “Negro womens children to serve according to the condition of the mother” (1662) and "An act for the purchase and manumitting negro Cæsar." (November 14, 1789)

Sometimes my training in economics allows me to explain just how remarkable a given document is. For example: “From Charlottesville. Land Improvement Company—Delegates Elected—Interesting Items.” (May 17, 1890)

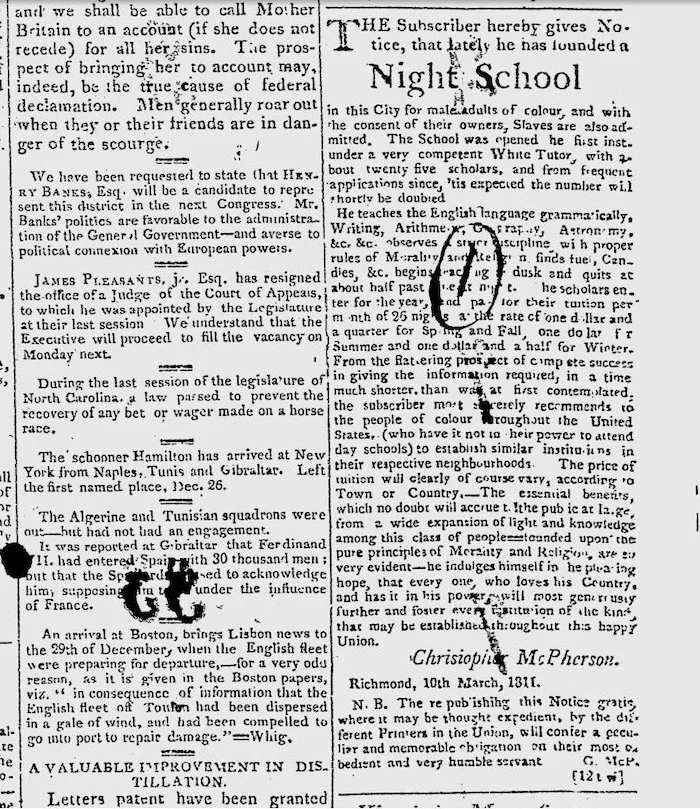

In other cases, by describing how multiple documents are connected to each other, I’m giving visitors a window into a conversation playing out over time and between characters, which is a direct way for visitors to sustain their own conversation with the past. For example: “Night School” (March 18, 1811)

Though we have standards for the truth of journalism, media literacy has historical and contemporary applications alike. In writing a heading for this article, it was important to disclose the leanings of the newspaper around suffrage: "Defence of Woman Suffrage" (March 18, 1870)

When we published an entry on Augustine Herrman’s map Virginia and Maryland As it is Planted and Inhabited this present Year 1670, I wanted to find a way to help readers see the subjectivity of maps and the role they played in colonization. After New Netherland leader Peter Stuyvesant dismissed Herrman’s proposal to make a map that would solidify Dutch sovereignty over the Delaware River, Herrman realized that the boundary-making powers of mapping might be appealing to divergent colonial leaders. In 1660, he made the same proposal to Cecil Calvert, second Baron Baltimore, who oversaw the Province of Maryland. Calvert accepted his proposal and in exchange, Herrman was given letters of denization, which formally provided the foreign-born trader and ambassador with trading and property rights. Therefore Herrman had incentives to draw a map favorable to his client and indeed to him personally as he soon afterwards purchased a tract of four thousand acres of land in the province of Maryland from the indigenous Susquehannock Indians. This throws into question the use of this map as evidence in boundary disputes between Maryland and Virginia ever since it was created.

In contextualizing the WPA slave narratives, which I’ve been adding to the Encyclopedia over the years, there are special considerations. Beginning in the 1920s, Black universities and colleges were already taking an interest in the histories that formerly enslaved people could tell and were documenting them. Later on, this work was taken up by the Works Progress Administration, founded in 1935 to transition millions of unemployed people on Depression-era relief rolls back to work. As part of the Works Progress Administration, the Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was assigned to create state-level initiatives to provide employment for writers. In Virginia and many other states, that included sending writers out to conduct interviews with more than 300 formerly enslaved people. Although in general the WPA discriminated against Black workers, in Virginia there was an all-Black unit of interviewers, supervised by Roscoe Lewis, which became the Negro in Virginia published in 1940. But still, in many instances, the interviewers were white. The racial hierarchy of the time influenced the content of the interviews. We know of some cases where the interviewer was the child of the person that had enslaved the interviewee.

When there is so little of enslaved peoples’ perspectives on their own experience in the historic record and most of the documentation that survives today was written by European and American enslavers, these narratives offer precious insights on how enslaved people built and interpreted their worlds from their folk life to their religion to the forms of resistance to their values. After all, as David Blight says, historians would love to know, what was it like to be enslaved? How did they psychologically survive? What were their daily feelings, yearnings, crises, and hardships?

As Gerda Lerner reminds us, the truth of writing an autobiography is that memory often suppresses painful, traumatic, embarrassing experiences, or what is not socially acceptable to readers. Our life-story changes over time as our understanding and our representation of our own life changes. Much of many autobiographies are made up of anecdotes, which are memories shaped to make a point, teach a lesson, create a character, embellish our tale with humor which serve the story.

With all of this in mind, I decided to think about how these narratives could offer a counterweight to the abstraction inherent in thematic entries in the Slavery section, entries like Slave Clothing and Adornment in Virginia, Slave Insurance, Slavery at the University of Virginia, Slave Housing in Virginia, Slave Literacy and Education in Virginia, and Slave Sales. Which narratives would personalize these historical and social concepts and processes?

I also came up with the following explainer for every WPA slave narrative header paragraph:

This interview, along with other Virginia Writers Project interviews, offer a composite portrait of interviewees’ self-styled personal stories. Interviewers’ interests, lived experiences, and editing choices, as well as their social relations and expectations shaped their relationship and conversation with the interviewees. Although the interviews aren’t unmediated autobiographies, they are no less authentic and are just as fruitful a source for reconstructing historical experience.

Some of my favorite interviews are: “Interview with Susan Broaddus” (Date Unknown)

“Interview of Mrs. Fannie Berry” (February 26, 1937)

A list of all the Virginia-based slave narratives can be found here.