I seem to be on an urban garden kick lately. But I find myself drawn to the communities that crop up around them.

The Urban Agriculture Collective of Charlottesville has so many facets and is forging community on so many levels that I decided to do a two part series on their work. Here's part one, which focuses on their unique economic model.

food

Growing New and Old Roots

Charlottesville is a town that prides itself on welcoming people from around the world–-among them many refugees. Some of those refugees are working on a farm that’s actually giving them the opportunity to enrich our community and help us rediscover our roots. I am so grateful to New Roots Coordinator Brooke Ray and farmer Samyan Raouf for showing me around.

via IRC Charlottesville's Facebook

Go to the Saturday market on Michie Drive 2-5pm!

Feasting on Eid al-Fitr

For the first time in a few years Ramadan seemed to pass me by without much thought, so with the end of month of fasting drawing near, I headed for Grand Market. This grocery store on Charlottesville's Main Street is run by an Afghan family and has been my source for the best tahini and dates since moving back to town. There I met the owner Abdul Rahim who warmly pressed me to try all the cookies on display for Eid, the holiday that marks the end of Ramadan. I felt torn between the disrespect of eating in front of someone in the midst of a 17-hour fast and not wanting to reject his generosity. I decided I couldn't say no. He was happy, I was happy. Food just tastes better during Ramadan.

I also met Fawzia and Shirin (not their real names) who so exuberantly shared memories of their favorite Eid foods.

Firni, the rice pudding that Fawzia and Shirin love to eat at Eid.

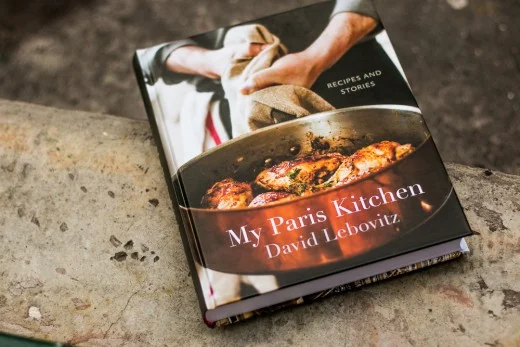

Authentic Cuisines with David Lebovitz

More than a decade ago David Lebovitz, a former pastry chef at Chez Panisse, moved to Paris and started writing about his life there on his blog and in many cookbooks. When I found out that he was coming to Charlottesville, I knew I had to find a way to talk to him. I have long read his blog as a voyeur on his life in Paris and for his excellent recipes (this orange-glazed polenta cake is killer). His latest book, My Paris Kitchen, is a nominee for a 2015 James Beard International Book Award. We spoke about why defining "authentic" cuisines is tricky business and why he embraces a more casual approach to cooking.

In our conversation, I mentioned how differently American-born chefs and immigrant chefs are portrayed on the scale of authenticity. Much of my thinking on this issue stems from a great exploration of the topic by Francis Lam and Eddie Huang. They hit on how standards of authenticity are related to power, class, media, and ultimately, why the representation of immigrant food matters so deeply.

Cooking with Angelo Vangelopoulos

For more than 20 years one local chef has been proving that food can be the means to connect us and foster community. Last week Angelo Vangelopoulos, chef and owner of the Ivy Inn, was recognized for his excellence when he was named a James Beard Award semifinalist in the best chef category.

via Our Local Commons

In addition to his enthusiasm for cooking, Angelo shared his passion for changing the American plate. Yes, Americans need to eat less meat but Angelo’s message is not just one of deprivation. Indeed, he finds himself more and more drawn to the complexity and rewards of cooking vegetables these days.

His hope for a more sustainable future stems from seeing a man revel in his market haul. He suggested that one day we might find a joy and entertainment in food rivaling that which our phones now provide.

A Bowl of Pho with Kinh Bui

In spite of the fact that Martin’s Tailoring is officially closed, the doorbell rings frequently. A constant stream of people comes through the door shivering and shaking off the cold of the rainy Saturday evening ready to don their fancy duds for the night’s festivities. One young girl sheepishly steps out of the dressing room in her cotillion dress. Meanwhile a professional dancer throws off her coat and changes into a floor length sequined dress. From their respective platforms both smile approvingly in the mirror, twirling around and imagining the evening to come.

Once the two women have indulged in their moment of vanity, the reality of their current surroundings sets it. The low ceilings of the workshop can barely hold the warmth emanating from the yellow walls covered with posters of the UVA golf team who have also taken their turn on these platforms. Vietnamese travel posters hint at the origins of the shop’s owners who quietly look on from the corner.

Kinh and Lan are standing, pin cushions at the ready, prepared to make any last adjustments. But the two tailors have already surpassed expectations. The women’s showers of praise are as glowing as if the pair had performed a miracle. And indeed the power of a well-fitting dress should not be underestimated.

Kinh does not suffer from any illusions of grandeur:

It’s a selfless sort of pleasure that is characteristic of this 50-something man. His life has been deferred in so many ways that he can very clearly identify the pleasures and joys in his life.

When I ask Kinh about pho, a soup that is as iconically Vietnamese as the hamburger is American, he recalls the recipe as a memory and a continuing source of comfort. “Pho and its aroma is my family.” Noodles and thinly sliced beef float in a spicy beef broth to which you add garnishes like jalapeno chile, mung bean sprouts, lime juice, fried shallots, and herbs as you slurp your way through the bowl.

Kinh met Lan when they were both students at the University of Agriculture in Saigon studying to be veterinarians from 1979 to 1982. They fell in love and decided to marry. But Lan’s mother did not approve of the relationship and did not trust Kinh’s devotion to her daughter. First there was the 4-year age difference. “She said to me, ‘you cannot love someone older than you’.” Then there was the issue of faith: “I was Catholic and she was Buddhist and her mom didn’t want us to marry.” At that time in Vietnam she wouldn’t have been alone in seeing faith as a defining feature.

At independence in 1954, the country was ruled by two different governments one communist in the north and another dictatorship in the south. These governments inscribed faith with new meaning. Kinh is from a family of landowners originally from the north of the country. After the communist government killed his grandfather and appropriated his land, his grandmother migrated southward, like many other Catholics.

The roots of pho mirror the migrations of this period. Originating in the north of the country it became popular in the south in the 1950s when those people fleeing communist rule brought the dish with them. In the south people added ingredients like green beans and different herbs, rau thom (literally translated as “fragrant leaves”).

After 20 years of rule by a regime in South Vietnam that favored Catholics, the communist takeover of Saigon in 1975 signaled a reversal of fortune for the country’s religious groups. One day on his way to school Kinh remembers seeing four coffins pass him and the next day four priests were executed in a square not far from his school.

“The communists used the stomach to rule you.” In the late 70s Kinh remembers eating sweet potatoes at nearly every meal. The government distributed food and with the exception of three days throughout the year, those rations did not include meat. On National Day, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, and April 30 (the fall of Saigon to the communists) each family was given horsemeat, which was imported from Russia.

At this moment when religion had political and economic ramifications, Kinh and Lan defied convention. Their relationship was a radical subversion of the doctrine espoused by both South and North Vietnamese governments that your faith defines you. In part the young couple was spurred on by the support of his father who was a teacher at the Catholic school in Saigon. “He always said that it’s your heart not your faith that matters. You may go to church or temple but the faith doesn’t affect your way totally. You are more than your faith. Even now my wife and I have different faiths.”

According to Kinh the quality of the pho hinges on the deeply flavored broth, which tastes better when it’s made for a crowd. The particular balance of this elixir cannot be achieved on a small scale. Indeed that may be why Pho is Kinh’s favorite meal. It’s fundamentally communal nature muddles any arbitrary divisions.

Under early communist rule pho and comfort were in short supply. Not only were ingredients hard to come by but state-owned kitchens took the place of most restaurants. According to Kinh this all changed in the late 80s when the Vietnamese government accepted US foreign aid. This brought greater access to a wider variety of food. Kinh was desperate for some pho. “You can eat pho every day at any time but I like to eat it for dinner because at that time the air is a little bit cooler and you can smell and taste it better.” It was the perfect excuse for Kinh and Lan’s forbidden rendezvous.

Given the fondness with which Kinh describes this nourishing soup, you might think that it was pho that weakened Lan’s mother’s resistance to marriage. But in the end she had in mind more practical concerns. In 1991 she and Lan went to the United States, joining her other daughter in the Charlottesville, Virginia. After a year and half in the United States Lan’s mother began to be concerned by her daughter’s prospects for marriage in their new home. At long last she conceded that Lan could return to Vietnam to marry Kinh. With the assurance that they would finally be together, Kinh found that waiting another five years for a visa was easy.

However, when Kinh arrived in Charlottesville in 1997, he found that his mother-in-law was still suspect of the marriage. “My wife’s mother lived with me and my wife. We took care of her. One day after 11 years she said to me, ‘you are a very good man.’ It was out of nowhere!” he laughs, still shocked to this day, before adding with smile, “but it was too late to get those 13 years back.”

Keeping the history of Vietnam alive is a priority for Kinh as he raises his daughter in the United States. He tells her stories of his youth and describes Saigon before it became Ho Chi Minh City but the most tangible aspect of his past is pho, which he continues to prepare in small batches for his wife and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Jennifer.

Regionally American : Linda Schoyer

Each year when Thanksgiving rolls around I look forward to my aunt Linda's Corn and Oysters, which is delicious in spite of or perhaps because of its roots west of the Mississippi, so far removed from the Pittsburgh roots of the rest of my family. No one in my family of non cooks would have taken the time to experiment in the kitchen long enough to discover that buoys of grey oysters bobbing in a sea of creamed corn and topped with browned saltine crackers crumbs deserve a place on the Thanksgiving table. When I pressed her on the traditionalism of this odd union, she insisted that it has been a mainstay of the holiday for generations throughout her hometown in northeastern Colorado.

But recently I discovered that this isn't just a local favorite. Last weekend my cousin overheard a shopkeeper in Slanesville, West Virginia complaining that the seasonal influx of orders for canned oysters had begun. So, I wondered, what made this dish a hit among people in rural mountainous regions that are so far from the sea? People who can only find oysters in a can no less? Once a year Linda dares to save more and live better by shopping at Walmart. “It’s sad but they’re the only place in Pittsburgh that sells them.” What possessed her and others to serve corn and oysters on a day when food with a family or community history tend to hold sway?

It turns out that it hasn’t always been this difficult to get oysters. Americans have long had a love affair with oysters. According to Mark Kurlansky's “The Big Oyster”, Colonists adopted the taste of Native Americans early on, eating the bivalves morning, noon, and night. They ate them pickled, stewed, baked, roasted, fried and scalloped and in soups, patties and puddings. To satiate the city’s “oystermania,” New Yorkers started farming oysters on Long Island in the late 1800s. This spurred the commercialization of the oyster industry. By 1880, New York’s oyster farms were producing 700 million oysters a year shipping oysters all over the country. (Kurlansky links this enthusiasm for oysters to the growth of New York into a great city.) So, perhaps it was at this moment of oyster abundance that mountaineers seized the opportunity to eat a dish inspired by what they imagined the pilgrims on Plymouth Rock might have eaten at that first Thanksgiving feast?

Or maybe this corn and oysters casserole represent an embrace of another part of the country? Was it a riff on the cornbread oyster dressings so often found on Thanksgiving tables in the southern coastal United States? This dish is after all the perfect expression of the region’s terroir, a nod to the imprint that the land, climate, and people have made on the cuisine. Prime among the products that inform the region’s singular cuisine is corn. According to the folks at Anson Mills, a company dedicated to reviving the heirloom grains that sustained the antebellum kitchens of the Carolinas, many of America’s native corn species have their roots in the region. What better complement to one of the region’s heritage agricultural products than the oyster, which thrives in estuaries where the fresh water from rivers meets the salt water of the sea? Recipes for this combination of regional goods abound. There are scalloped corn and oysters from Virginia, oyster-cornbread dressing from Louisiana and Alabama, and even Corn Oysters (which are corn fritters that resemble oysters).

Linda isn't sure how the dish made it's way onto her family's thanksgiving table but she was happy to share the recipe, beginning with this disclaimer: “I’m almost ashamed to tell you the recipe because it’s so simple.” Nevertheless here she is recalling the method:

(That laughter at 27” is yours truly imagining my version of “however much butter you like,” which is mountain-sized.)

Simple it may be but her casserole was good enough to win over my notoriously opinionated grandmother who requested it every year afterwards. On second thought, perhaps she warmed to this casserole that was so exotic to her Allegheny roots because of her love for the humble saltine.

Those butter-bathed saltines give the dish a nice textural contrast which could be a kitsch vestige of the 1960s but the crackers actually have their origins in the 19thcentury. Their story begins with Frank L. Sommers of St. Joseph, Missouri, a baker who made them for a 1876 county fair and won the blue ribbon for his creation. In 1890 the reach of the saltine cracker expanded when Sommer’s company mergedwith several other midwestern bakeries to form the American Biscuit Company. With the 1898 merger of American Biscuit Company and the New York Biscuit Company (later known as Nabisco) saltines began to be sold nationally.

Although the saltine cracker quickly became the antidote to upset stomachs across the country, these days the coupling of oysters and corn is less amicable. Renewed support for oyster farming is reviving colonies in the Chesapeake Bay but it’s a struggle in the context of competition with watermen for territory. In the Mississippi Delta, the threat is more nebulous. Fertilizer runoff from corn farms in the Midwest flows into the Mississippi River where it has boosted algae and microbe growth in the Gulf of Mexico. The algae and microbes have consumed all of the oxygen in 5,800 square miles of water offshore, killing other marine life and creating the second largest deadzone in the world. Even in coastal regions where oysters reside, this nutrient-rich runoff has created low oxygen conditions, which weakens oysters’ ability to fight off disease. In the context of this toxic relationship between corn and oysters perhaps Linda’s casserole represents the remaining opportunity for these two staples of the American harvest to share a stage.

Our rebuff of Linda’s contribution to the Thanksgiving table as a regional oddity may have been misguided. You could say that in this dish we can see both the promise of American abundance as well as the consequences of a misguided use of our land and native species. What better day to remind us of the country’s diverse roots, of the human and agricultural kind alike, than on Thanksgiving? Well, that and you would be hard pressed to find a better way to showcase the potential greatness of a saltine.

Questions of Authenticity: Diwan Damas

When read about a place in London that was making booza al-haleb, a Syrian pistachio ice milk, I knew how I would be spending my afternoon. But when I got to Diwan Damas it seemed that my culinary quest for this treat, so rarely found outside of the Middle East, might have been in vain. Aside from a shocking neon blue bubblegum flavor, the ice cream freezer outside the shop was filled with chocolate, hazelnut, vanilla, and other familiar flavors. I tried to not look too disappointed as the shopkeeper bounded forward, eager to serve me. When I inquired about the mythical booza al-haleb, he smiled and pulled out what looked like a white Swiss roll studded with pistachios from behind the counter. He explained that whereas ice cream is made by whipping air into a custard base, booza al-haleb is made by kneading the air out of frozen milk that has been thickened with mastic gum, the resin of an evergreen shrub, and sahlep, the powdered root of the orchid. They form this stretchy mixture into thick slab, cover it in the most flavorful Iranian pistachios, and roll it up. I watched as he sliced one end off, gave it a twist and popped it in a cup. “This is the only place in Europe where you will find booza al-haleb.” Without the air it melts very slowly, giving me ample time to check out the other wonders of Diwan Damas with Mahmoud* as my guide.

The view is a seemingly endless landscape of brown and green— tray upon tray of bronzed pastries topped with chopped pistachios. I needed a guide to recognize the rich variety of what was on offer. We began with katayef, fluffy pancakes that are filled with either slightly salted cheese or chopped walnuts, sugar, and cinnamon and then drizzled with a lemony syrup. Next door was a platter of Awwammat, which positively glowed from their two baths: first a dip in hot oil followed by a sugar syrup soak. As Mahmoud said, an awameh is like childhood: so intensely sweet you can’t imagine having more than one. A dose of cream is in order and for that we have to head to central Syria.

According to Mahmoud, pastry chefs in the city of Hamah are known for their use of ashta, a cousin of clotted cream. Shabiyat, are a perfect expression of that tradition. Crisp layers of phyllo dough are folded over a dollop of ashta and dipped in pistachios. Moving down the counter, and geographically south, we encountered the specialty of Homs: halawet al jeben, mild cheese pancakes stuffed with cream. In this sea of cream, it was hard to ignore a tray of bright red kunafa.

The color denotes that this is kunafa nabulseeya, that is, kunafa from Nablus, Palestine. Something like an inverted pie, the unifying feature of kunafa, in its many expressions, is the contrast between its two layers. Mahmoud points out that Arab sweets are all about balance between contrasting textures and flavors. The top layer of kunafa is a crust of either a fine semolina or a thin noodle like pastry, which confusingly is also known as kunafa, or both. The bottom layer is either a mild cheese or cream. Served warm with a dusting of pistachios and drizzle of syrup, the creamy layer softens and stretches beneath the crisp shell.

At first I had the impression that I had stumbled upon a hidden gem but with the setting sun came a constant stream of customers. Some stopped in for a chat and a man'oushe, a savory flatbread topped with za’atar, a spice blend of thyme, hyssop, sesame seeds, and sumac. The only chair in the shop, squeezed into the shop’s only vacant space, offered one lucky customer the opportunity to enjoy a warm slab of kunafa. Customers who felt guilty about even entering a sweets shop were assured that the kunafa diet would be the next health craze. While the size of the shop wouldn’t allow for the diwan, or assembly of a governing body, that the name suggests, there is palpable spirit of communing about the place. Each customer is greeted with such warmth that you would think everyone was a regular.

The integrality of customers to the shop extends to minutiae of the pastries themselves. When he began hearing complaints about the flavor of orange blossom water overpowering the baklawa, Mahmoud decided to try making it without. Since then they have stopped adding orange blossom water to the sugar syrup that they brush on the baklawa. While other stores are “taking advantage of nostalgic people who might settle for less flavour to recall a dazzling memory” Mahmoud isn’t concerned with sticking to tradition. Instead they’re striving for great bakalava, which should be, “crunchy but also soft--it melts on the tongue.” At its best, baklawa, is a perfectly engineered ratio of buttery crisp phyllo dough to roasted nuts brushed with only a small amount of sugar syrup. I usually find baklawa to be cloyingly sweet and soggy but according to Mahmoud I have been shopping in the wrong places. If you see pool of liquid at the bottom of the baklawa tray you know the bakers are dousing the pastry in too much simple syrup or clarified butter. "They're probably trying to hide something: dry phyllo dough or poor quality pistachios." The cashew-filled assabeh I tasted at Diwan Damas was just barely sweet and astonishingly light. With no soggy bottoms in sight I hardly missed the orange blossom water.

Indeed, challenging the restrictions of tradition seems to be characteristic of the shop. Although orange blossom water is traditionally an integral component of baklawa, like any business, Diwan Damas is making efforts to respond to the tastes of its customers. The difference is that by physically operating outside of these traditions, it has become a collaborative enterprise based on an ever-evolving notion of excellence.

The communality of this experimentation is also apparent when Arabic speaking customers assume a Damascene accent and vocabulary regardless of their own origins. This nod to the "Damas" in the shop’s name, which refers to Damascus, the birthplace of nearly all of the employees, is not the means for recreating an authentically Damascene experience. Rather it is a form of collective creativity rooted in the city’s ethos of openness. Mahmoud recounts how he and other employees often sprinkle their conversations with phrases that are local to the customer's homeland. This mutual posturing is a conscious effort on both sides but the result is a genuine intimacy. It’s as if through this linguistic jostling, geographical boundaries are blurred and a club based on a shared love of pastry, one that is unique to 121b Edgware Road, can bloom.

So often authenticity is the highest form of praise for foreign food. But no matter how much effort goes into faithfully reproducing a dish, ultimately food evolves with the experiences of the cook and the interests of the customers. While the people behind Diwan Damas are clearly committed to preserving tradition, to say its “authentically Syrian” obscures the stories and passion behind every pastry on their counters. In the words of Eddie Huang, “what’s authentic is when you make something that is authentic to your experience.” In the case of Diwan Damas those experiences are giving rise to a community and superior pastries.

*This is a pseudonym.

Serving up Pepper Soup for the Graduate Student Soul: Chris Anojulu

Social gatherings at the Sidney Webb graduate student accommodation are few and far between and when they do occur, the limited degree to which students do know each other is evident in the gasps of surprise as classmates realize they have been next-door neighbors all term. Graduate school is, after all, an inherently selfish endeavor. For many it’s a retreat from the vagaries of professional life demanding such concentration that there’s a tendency to embrace a monk-like existence, totally devoid of social interaction.

And yet, from behind the building’s reception desk, there is one adult who is drawing students out of this bubble and keeping them connected to the real world. Although his official title is security guard, Chris Anojulu acts as part time social director and guru for the 500 angsty twenty-somethings that call this place home.

Even if they don’t all know his name, every resident knows, “the friendly guy in reception.” It’s rare that someone passes his desk without a pound of intimacy, warm exchange, or at the very least, a nod of acknowledgment. Even those who started the year not looking him in the eye or slamming the door turned were softened by Chris’ good humor. “You cannot make instant judgments because those people actually turned out to be the nicest ones—I just caught them at a moment when they were going through their own stuff.” Throughout his daily night shifts, he offers wisdom and spurs generosity among this inward-looking crowd.

He gives people the benefit of the doubt almost to a fault. Even his remarks that people never seem to be satisfied with their lot are made in a spirit without reproach. “When the weather is hot, they complain. When the weather is cold, they complain. This year I decided I’m not going to complain about the weather at all.” Thwarted by the 3 or 4 people who have already come by that day and said, “can you believe the heat?” he just laughs. “I know they do it because they just want to have a chat, but how many conversations can you have about the weather?”

Just as he finds something to laugh about in exchanges about the weather, he generously responds to the hundreds of questions he is bombarded with each day as if they were unique: “My roommate has a fever, what should I do?” “Help! My toilet is overflowing.” “Where can I order burgers from?” Ever since management replaced the coin operated laundry machines with an online system, the questions pertaining to washing clothes are never-ending: “The laundry machine says, ‘DE’. What is it trying to tell me? What setting should I use to wash my underwear?”

His attentiveness to these queries conceals the fact that he has dealt with the same issue only moments earlier. Instead of disparaging these questions, he attributes them to a particular time in life. “When you’re young you sleep a lot because you don’t have worries but when you’re an adult you have responsibilities and sleep isn’t as important. You grow to need less sleep.” For him, these expressions of the carelessness of youth are a reminder that adulthood demands proactivity and an end to complacence.

Coupled with his penchant for positivity, Chris is keenly aware that a healthy douse of realism does everyone some good. When students nearing graduation bemoan their reentry into the job search, he has little sympathy. “You want to know how to succeed? I’ll tell you how: be smart, struggle, hustle, and work hard.” He attributes his own success to this mantra. When he arrived in Germany from his native Nigeria and in London after that he took every odd job he could find from picking green beans to dry-cleaning.

“Give me 6 months anywhere and I will have it figured out. The mistake people make when they arrive in a new country is to try to get the top job. Just take any job and figure out the system. Once you’re in the system you’re set.”

It’s just this sort of intuition that makes him such an attractive figure. His knack for grasping a person’s character has garnered him quite a following including a group of students who would hang out at the reception desk for a few hours every week. They would chat openly about their girlfriends asking him for his advice on their relationships. With their departure came the end to their friendship.

Indeed with students coming and going every day and a new batch arriving each year, Chris remains the one constant in the midst of transition. Although he acknowledges a feeling of loss at the end of the school year, he is constantly facing forward. It might be easy to dismiss his abundant adages as hot air but he lives what he proffers.

“If anything ails you, just find the pepper soup recipe that suits. Drink a bowl of it and you will be cleared out and ready for the next thing.”

An Elective Affinity wth Paris: Catherine Down

Anyone who claims that the French are unfriendly has never seen Catherine Down in action. She buzzes around the streets of Paris, bringing every corner to life with tales of its specialty food shops and restaurants and characters behind them. “Let’s get some schwarzbrot from Benjamin… Laurent’s shop is so special because he not only sources but also ages the best cheeses…we should go to the herb man for our goat cheese spread.” Indeed every morsel we share in Paris conjures up a story. And given Catherine’s penchant for talking quickly and my stomach’s infinite expandability when it comes to pastries, this added up to a lot of stories.

Just as Catherine makes every walk a food tour, the streets of Paris themselves seem to demand that attention be paid to the city’s unreal food. You can’t help but notice the deli cases at Ramella, overflowing in an abundance of beautiful tortes, soft poached eggs in aspic, pâtés, and quiches that physically extend the shop beyond the façade and onto the sidewalk. We took the bait; the clerk smiled grandly, likely recognizing Catherine as much for her frequent patronage as for the enthusiasm with which she orders her roasted veg salad and stuffed peppers.

Butchers too capture public space by planting their rotisseries on the sidewalk, offering culinary street entertainment and a scent that Catherine declares to be, “the smell of Paris.” If you don’t salivate as you walk by the dozens of rotisseries filled with roasting chickens dripping fat on potatoes, life is calling you. Similarly the smell of butter wafts out of corner bakeries and patisseries and onto the streets, never letting you forget to enjoy your daily bread (or croissant, chausson aux pommes, madeleine etc.).

She inhabits the place so naturally that I have to remind myself that this is her adopted city. Before moving to Paris in 2013 she got her masters degree in Food Culture and Communications at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy and at 24 years old she had launched and edited a magazine. Now she is the Assistant Editor of Paris by Mouth, a website about the city’s food and wine. As she puts it, “my whole life is based on the conviviality of food.” In addition to her work on the website, Catherine leads food tours, which she likens to hosting a dinner party four or five times a week.

To my queries of where to find the best baguette, she gave me the addresses of some of her favorites but ultimately she said the best baguette is from the bakery closest to wherever you’re going to eat it. With no preservatives, baguettes go stale about 5-6 hours after they come out of the oven. Croissants are similarly beholden to this temporality. Catherine often times her arrival at one of her favorite bakeries to coincide with the time when the second batch of croissants comes out of the oven. 10:45am on the dot.

The near evanescence of French food comes up again and again in our conversations. When she first arrived in Paris Catherines says she would complain about food going bad so quickly, but now, “I realize that’s something to aspire to. When I think about things I love about Paris, they’re ephemeral.”

Among those fleeting tastes are éclairs, which she suggests should be eaten for breakfast before the pastry cream softens the chou pastry over the course of the day. For the ultimate expression of instant gratification, she directs me to La Maison du Chou where they make one thing and one thing only: choux à la crème(cream puffs). They bake their choux twice a day, filling them to order with a light cream made delightfully tangy with the addition of fromage frais.

On the other side of the Seine, Jacques Genin is wholeheartedly invested in preparing food to be eaten and enjoyed right away. Despite my excessive use of positive superlatives to describe my time in Paris, Catherine is judicious with her approbations. But when it comes to Genin, her effusiveness knows no bounds, “everything he touches really does turn to gold.” After tasting his Paris Brest, lemon basil tart, and vanilla millefeuille, I would have to agree.

His pastries are not available to take away and one cannot even visually enjoy them as they do not sit in cases waiting to be consumed but rather are made to order. The millefeuille arrives at our table after being assembled in a workshop upstairs and carried down to the tea salon via a spiral staircase in the middle of the shop. This descent is the literal expression of a transcendental experience, a reminder that this is more than just food. Yes, the crispness of the puff pastry layered on the soft, just piped buttons of pastry cream means that with the application of your fork, the tower shatters—Catherine assures that me that “there is no elegant way to eat this”—and you taste the most marvelous contrast in flavors and textures. But even more than that, the entire ceremony around the preparation of the millefeuille makes you acutely aware of the moment and its intangibility.

Perhaps that’s why meals in Paris are so much more than calorie consumption. There would be no place in Paris for Soylent, a slurry of the 35 nutrients required for survival, intended to respond to what its founder sees as, “a separation between our meals for utility and function, and our meals for experience and socialization.” That’s a false dichotomy in the Paris that Catherine showed me, where people were embracing the summer weather by spending more time outside, to a large extent commensally. And sociality isn’t even limited to one's dining partners. Whether people are gossiping over espressos and cigarettes with a view of six streets converging at Café Le Progrès or sharing falafel with a side of smashed cauliflower overlooking the kitchen at Miznon or licking cones of Berthillion caramel ice cream at the tip of Île Saint-Louis while overlooking the Seine, they are engaged with the world around them.

One evening we sat in her living room and consumed a mound of perfectly ripe cherries and apricots (this in spite of the fact that Catherine is allergic to raw fruit because at this time of year “they’re worth an itchy throat”) while she recalled one of the many occasions on which she realized that economics among the shopkeepers of Paris is not governed by profit alone. Earlier that week Catherine bought a cherry tart from her neighborhood bakery and finding it to be quite good she returned the next day for another. The shopkeeper, incredulous at her request, responded with, “encore (another)?!” At expense of selling more pastries, she would rather express concern for the wellbeing of or more cynically, judge the eating choices of her customers.

Our breakfast of kouign aman, a caramelized pastry from Brittany (and surely the reason butter exists), had me convinced that the rest of the day could only go downhill from there but Catherine knows better: for her each day in Paris promises adventure and mango caramels that “will you ruin you for all other caramels.” After all, it is in Paris that Catherine has found people who are equally zealous about what they’re doing with their lives.

Over steak frites bathing in the most glorious green sauce, Catherine bemoans the fact that so many women are in relationships with men, “who are simply not worthy of the air these women breath.” While she can imagine a time in the future when she might want to be taken care of, right now the thought of compromising on where to live and what jobs to take is mind boggling. “My two top priorities in life right now are cheese and vacation so, where else would I go?” Indeed, why settle for anything less than Paris?